When twisted justice stops prisoners from starting over

In U.S., men, women, children get caught in revolving door of incarceration at rate that exceeds nearly all other nations

The first in a series of multimedia projects that examine causes for recidivism in the American justice system.

After Casey Irwin, 37, was released from prison, she worked a string of low-wage jobs that made it nearly impossible for her to pay the rent or put food on the table for herself and her two kids.

Irwin's criminal record prevented her from getting affordable housing. She applied for higher-paying jobs, but her lack of education (she dropped out of high school) and history of incarceration limited her work options. Her husband was still in prison on the fraud charges that had gotten them both arrested.

After several years of trying to make it with little support, she fell into a lifestyle she knew would make quick money — selling drugs. The lessons she was supposed to have learned during the drug treatment program near the end of her seven-year sentence did little to help her survive. In 2014, Irwin returned to prison for drug possession, this time for more than a year.

"The first time I went to prison, I didn’t learn anything about myself, I was just surviving," Irwin said. "What I found out, when I got out ... no one talked about behavior change or why I was making those decisions I was making. I didn’t have anybody forcing me to take a look at myself."

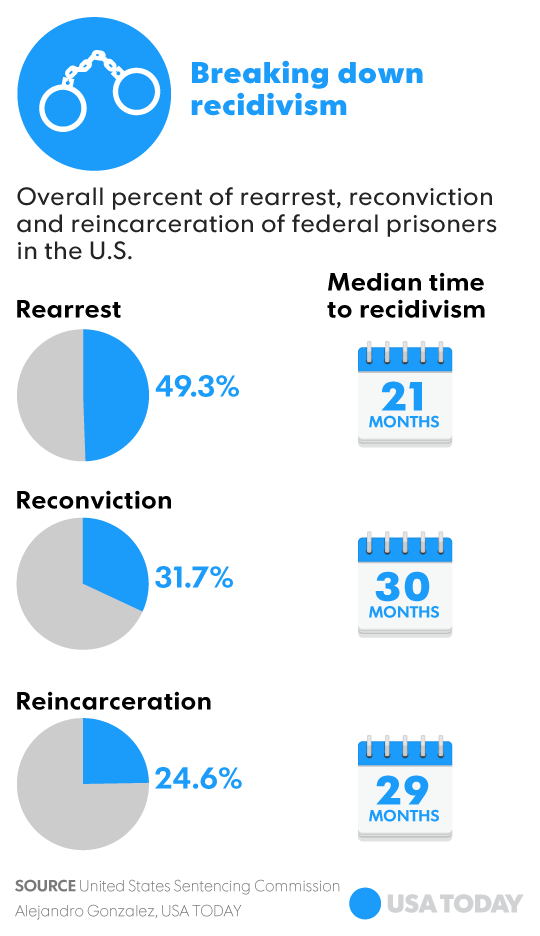

Irwin's story is like that of so many others who get stuck in the revolving door of the U.S. prison system. America not only incarcerates its citizens at a higher rate than almost any other nation, it also has one of the highest rates of recidivism (defined as any run-in with the system through reconviction, rearrest and/or reincarceration) in the developed world.

Men, women and children all get caught in the system at high rates, and they do so in different ways.

Men return to prison more frequently than women do. But when women re-enter society, they often face issues that affect job stability, including difficulty finding child care. Kids who land in juvenile detention are more likely to return to the system as adults.

The U.S. has one of the most restrictive justice systems in the world. Inmates are sentenced longer than in most countries and for infractions that elsewhere may not even bring jail time. More than 300,000 offenses are considered criminal in the U.S.

And after inmates leave the system, there are 48,000 legal restrictions that make it difficult for most to rebuild their lives. People with a criminal record are often barred from accessing housing along with certain jobs and professional licenses. In Washington, D.C., a person with a criminal record is ineligible for housing vouchers. In Wyoming, former prisoners are ineligible to operate a funeral home or hold certain county and municipal offices. In Missouri, some former convicts can’t work in a state agency. Ex-offenders are often hindered from voting.

For many, excessive restrictions make starting over difficult, if not impossible.

More hurdles for women

Piper Kerman spent more than a year in a federal women's prison on drug charges. Kerman has dedicated much of her life since her release to inmate outreach and wrote about her experiences in Orange is the New Black, which was turned into a hit Netflix series. When women (who are often the primary caretakers) go to prison, their children are often left much more vulnerable than when men enter the system, Kerman said.

Indeed, Irwin left her two kids with her mother when she was rearrested in 2014. She had little connection with them during her incarceration or her stint in a halfway house when she was transitioning out of prison.

More than three-quarters of former felons are rearrested within five years of their release, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics. On the federal level alone, about 45% are arrested again. Those who are more likely to be rearrested haven't finished high school and are under 21, African American and have been convicted of crimes involving guns, according to a 2016 report published by the U.S. Sentencing Commission. The data also showed that of the federal offenders released in 2005, when the study began, more than half were rearrested within two years.

When Chandra Bozelko was released from prison in 2014, her parents picked her up and took her to their home where she had food, clothing and anything else she wanted. The 1994 Princeton graduate had served six years for identity theft. Like Piper from the hit show Orange is the New Black, Bozelko, a New Haven, Conn., native, grew up in an upper middle-class family. Her father was an attorney and her mother, a nurse in the New Haven city school system.

While Bozelko's advantages made her transition to the outside world easier, she still struggled.

She was turned down dozens of times before finally getting her first job offer. She neglected to mention her criminal record. That employer rescinded the offer after a background check.

Still Bozelko, now a 44-year-old non-profit consultant, knows she is privileged. Many who are released don’t have family support or money for food, clothing and shelter after incarceration.

Finding and keeping work is generally more difficult for women than it is for men.

Nearly a third of incarcerated women return to prison during the first few years following their release, according to a report on women and recidivism. About 33% of women are employed six months after their release, but they often lose their jobs because they can't get child care, they face discrimination or have conflicts with employers.

In some states, certain felons are barred from more than 800 occupations, according to the 2015 Center for American Progress report “Removing Barriers to Opportunity for Parents with Criminal Records and Their Children: A Two-Generation Approach." More than 60% of former felons cannot find work a year after being released. And men are paid an average of 40% less than employees without a criminal record.

Rebecca Vallas, managing director of the Center for American Progress' poverty-to-prosperity program, helped craft the report.

“While most attention over the past several years has been paid to the need for sentencing reform ... we will fail to solve the larger set of problems if we ignore the need to remove barriers to re-entry that people face when they're returning to their communities and trying to get back on their feet,” Vallas said. “That’s really going to be critical to break the cycle of recidivism that can so often result when people find every door closed in their face while they're trying to do everything right and get back on their feet.”

Incarcerated kids become incarcerated adults

Johnny Perez was 16 when he was first incarcerated at Rikers Island, an adult prison in New York reputed to be one of the most dangerous in the country.

His crime? In 1996, he was arrested for gun possession and sentenced to a year in prison.

Now the 37-year-old is a safe re-entry advocate for the Urban Justice Center.

While New York's laws on juvenile incarceration have changed, teens get sentenced as adults, like Perez did more than 20 years ago, all too often. About 34,000 young people are in facilities throughout the nation. And 4,500 youth are locked up in adult prisons; approximately 600 juveniles are incarcerated because of “status” offenses such as truancy or running away, according to the Prison Policy Initiative.

And kids who get locked up run a greater risk of becoming incarcerated adults.

►MORE FROM PEREZ:Invest in education instead of incarceration: Voices

Perez returned to Rikers five years after his first stint in the prison. At age 21, he was incarcerated for robbery and served 13 years of his 15-year sentence. The activist is currently out on parole. A high school dropout with a criminal record, Perez felt that he had limited employment options, he said, and that the educational system in his neighborhood didn’t embrace him, a young boy of color.

“I wonder what I could have been if they had invested in me — saw my potential,” Perez said.

Some states are working to reform their juvenile justice policies. Connecticut has a long history of juvenile justice reform including alternative programs to incarceration and improved conditions of confinement. Gov. Dannell Malloy has proposed a reform package that would expand Connecticut's jurisdiction for juvenile courts to defendants up to age 21. New York's Raise the Age law, which fully takes effect in 2019, prevents 16- and 17-year-olds from being automatically prosecuted as adults.

Adam Foss, a former assistant district attorney in Boston, created programs he felt would address the issue of incarceration at its core. These include a literacy program for kids, a program that gives young men alternatives to incarceration, and another that funnels young adults into community programs.

“I saw people failing on probation all the time, and going to jail for stupid things that we, as the government, could fix,” Foss said. "If my job is to improve public safety, if my job is to do justice, then we need to be not only paying attention to this case that's right in front of us, but (also to) what happened to these people before they got here."

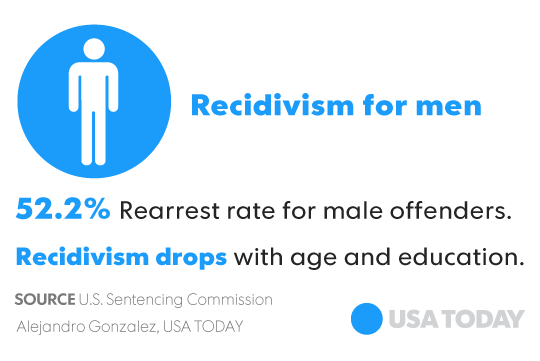

Men return at higher rates

Blacks are more likely to return to prison than whites, and men are more likely than women to return to prison (52% of men return and 36% of women go back).

During his nine years as an assistant district attorney, Foss saw a disproportionate number of black men enter the courtroom. The criminal justice system punishes people without addressing issues that cause them to commit crimes in the first place, Foss said.

“We send them to places that are resource-poor, and very traumatizing. We provide some classes in there (prison) and some programs in there, but imagine yourself being confined to the same building for years at a time, and how well you would respond to education in those settings. It's just unnatural,” said Foss, who now heads the organization Prosecutor Integrity founded by singer John Legend. “Those programs don't really set them up for anything. Then they come out, they're not given any sort of support, and they're put back into the community they offended in. When you have that combination of things, it's no wonder that we continue to fail. Education, employment, housing and treatment are the four hallmarks of a really strong community. You don't get any of those in any part of the criminal justice system.”

Addressing social problems, Foss said, not continuing to put people in jail, will help decrease recidivism.

“I think what could curb recidivism is understanding that recidivism is just literally repeating the behavior that got them there in the first place,” he added. “We need to understand that every touch point that we have in the system, that this is a problem to be solved. We have evidence, and we have tools, and we have interventions that work to solve them. It's not jail. We have to stop relying on that as the only tool that we have in our shed.”

Lottie Joiner is a 2017 John Jay/Harry Frank Guggenheim Crime Reporting Fellow and a Fund for Investigative Journalism/Schuster Institute Social Justice Investigative Reporting Fellow.

Visit Policing the USA for more podcasts, videos and comments from Kerman, Foss and Perez and interviews with male, female and juvenile inmates across America in coming installments of this series.