The missing numbers in Roy Williams' record book

North Carolina is happy to tout a laundry list of Roy Williams’ numbers. Wins and ACC titles, for example. Or Final Four appearances.

(This is two in a row, for those counting, and fifth in 14 years.)

There’s one number, however, on which North Carolina is noticeably silent: Williams’ total compensation. Specifically, the money he gets from outside sources. That includes money from shoe contracts, basketball camps, speaking engagements and TV and radio shows — sums that surely dwarf his base salary.

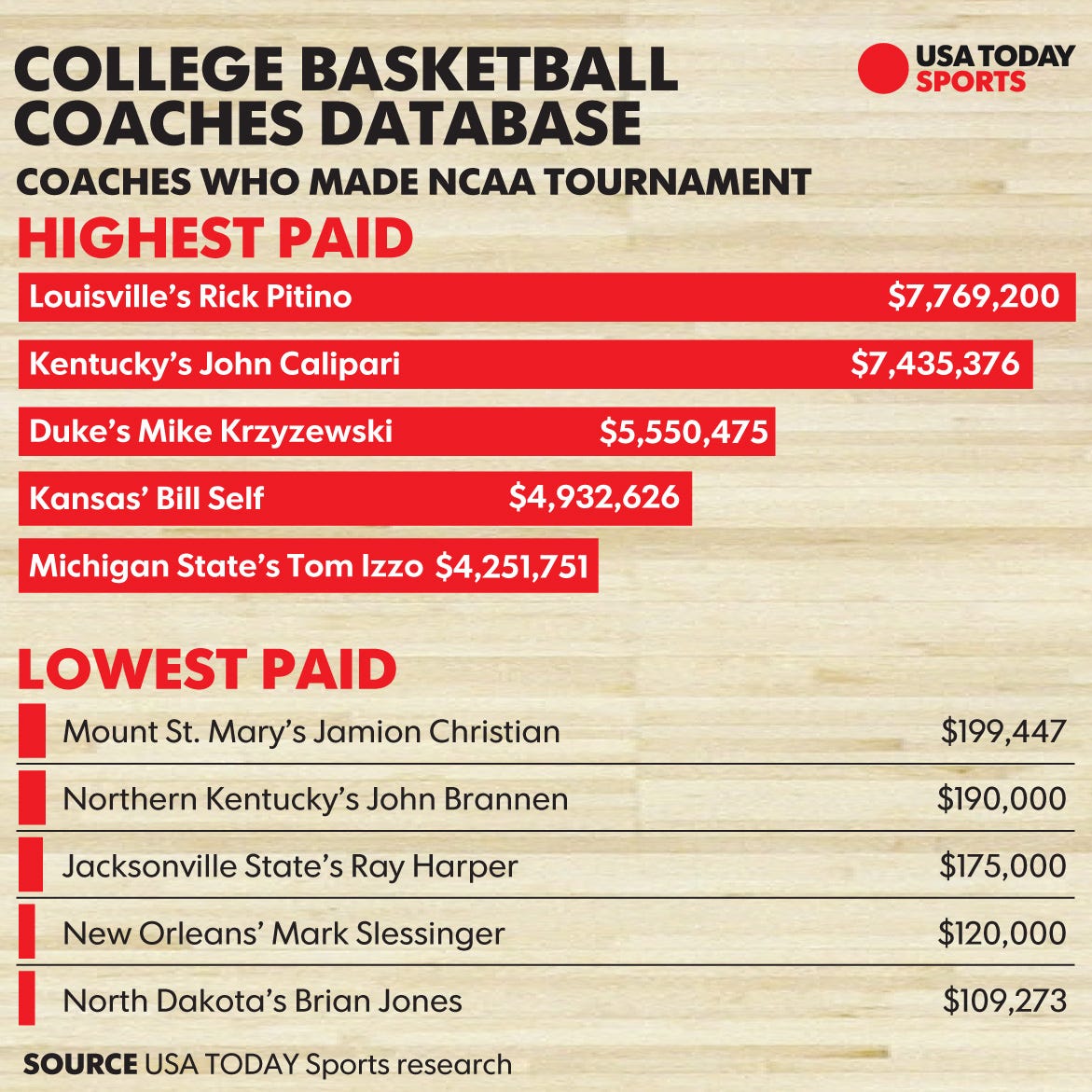

What NCAA tournament coaches make: Salary database

Williams and North Carolina aren’t alone, either. An annual review of coaches’ pay by USA TODAY Sports found more and more state schools have stopped collecting information on outside income and benefits paid to their coaches.

“Coaches are going to hit $10 million a year,” said Dan Rascher, a sports economist who is the academic director for the Sport Management program at the University of San Francisco. “That’s just crazy. Regular people are going to be like, `What is happening?’ So I think part of this is trying to slow that train down or keep our eyes off of it.”

The NCAA used to require schools to collect information on income and benefits that any athletic department employees received from outside sources. Most schools would disclose that information but some, including North Carolina’s flagship university, refused.

MORE COACHES COMPENSATION COVERAGE:

NCAA Final Four may illustrate some of coaching's big perks

Louisville's Rick Pitino breaks own record for outside income

Why Virginia Tech has bet big on coach Buzz Williams

Tired of policing what could range from a single pair of shoes to a multi-million shoe contract, the schools’ representatives on Division I’s top governing bodies dropped the reporting requirement last spring. Lo and behold, with no obligation to track the extra income, many schools are deciding they can’t be bothered.

This isn’t pocket change, either. South Carolina’s Frank Martin gets a cool $1.9 million for endorsements and radio and TV appearances. That’s in addition to his base salary of $350,000 and a supplement from the school of $200,000.

Technically, Martin’s $1.9 million is not considered outside income because South Carolina negotiated the deals and they were then written into Martin’s contract. But that’s just legalese. He’s getting paid by outside entities, just as Williams is.

And considering Williams’ accomplishments — and the fact his base compensation of almost $2.1 million this year ranks 24th among the 63 coaches whose teams made the NCAA tournament and for whom financial information is available — it’s safe to say he’s getting at least what Martin is from outside sources and probably more.

Much more.

But we won’t know because North Carolina won’t make it public. Won’t configure Williams’ contract to ensure the outside income is transparent, either.

“It’s uncomfortable for them and creates lots of questions. Why is the highest-paid employee in the state often a head football coach?” said Rascher, who has testified against the NCAA in cases involving economics. “So I understand why they want to keep this information hidden from the public.

“But at the same time, they are government employees, and these payments pertain to jobs as government employees.”

Now, it’s true the money from the side gigs isn’t coming out of the pockets of taxpayers. But that’s beside the point. The money, as Rascher said, is a byproduct of being a state employee. Or, as the old saying goes, the name on the front of the uniform is a heck of a lot more important than the one on the back.

Sure, someone like Williams could retire and still command a contract from Nike or have kids lining up to attend his basketball camps. But he’s one of a small number of coaches who could do that. Most have drawing power because of the school they represent.

A school that’s funded by taxpayers.

Think about it this way: If a governor or state legislator was getting money from outside sources, particularly companies or people who could influence their decisions, there would be a ferocious uproar if the details weren’t disclosed.

Why should the outside income and benefits these coaches get be considered any differently?

“On the surface, it doesn’t matter. But it gets down to, to me, fundamental fairness,” said B. David Ridpath, an associate professor of sports administration at Ohio and fellow at the Center for College Affordability and Productivity.

“How much control does that outside entity have over that coach? … Who’s having influence?” asked Ridpath, the compliance director at Marshall from 1997 to 2001. “That always worries me, and I think we need to be completely upfront from where these payments are coming in.

“We would worry about it if it was the mayor, we would worry about it if it was a congressman,” Ridpath added, “and I think we should ask the same questions of who’s really controlling college athletics.”

Oh, we have. With nothing requiring schools to track outside income and benefits anymore, however, don’t count on many answers. Or anything close to transparency.

It’s all well and good to brag about wins and losses. But those aren’t the only numbers that matter.