Why Virginia Tech has bet big on coach Buzz Williams

BLACKSBURG, Va. — The meeting was a long one, spanning three exhaustive days that ended at Buzz Williams’ home in Milwaukee in which a basketball coach obsessed with contract clauses and an administrator trying to make a program-changing hire were poring over details without the input of agents or attorneys.

If it didn’t work out, Whit Babcock, who had just been hired himself as Virginia Tech’s athletics director, would presumably slink out of town and move on to the next coach without anyone being tipped off to his plan. But if it did, a program that had languished at the bottom of the Atlantic Coast Conference would not only be changing coaches but its entire level of investment in basketball, stretching its budget to the absolute limit in order to lure a proven winner.

Williams, who keeps a daily diary and organizes every detail of his life, brought six years’ worth of notes to the meeting with Babcock covering all of his prior contract negotiations with Marquette, serving as a blueprint for what he would need to transform Virginia Tech from doormat to winning program in the nation’s toughest conference. Every detail was covered from recruiting budgets to staff salaries to the number of tickets he would get at Hokies football games. By the third day, even as Babcock put a deadline on the negotiations, Williams insisted they push through to the end, just to make sure nothing was left in the gray area before he decided to take the job.

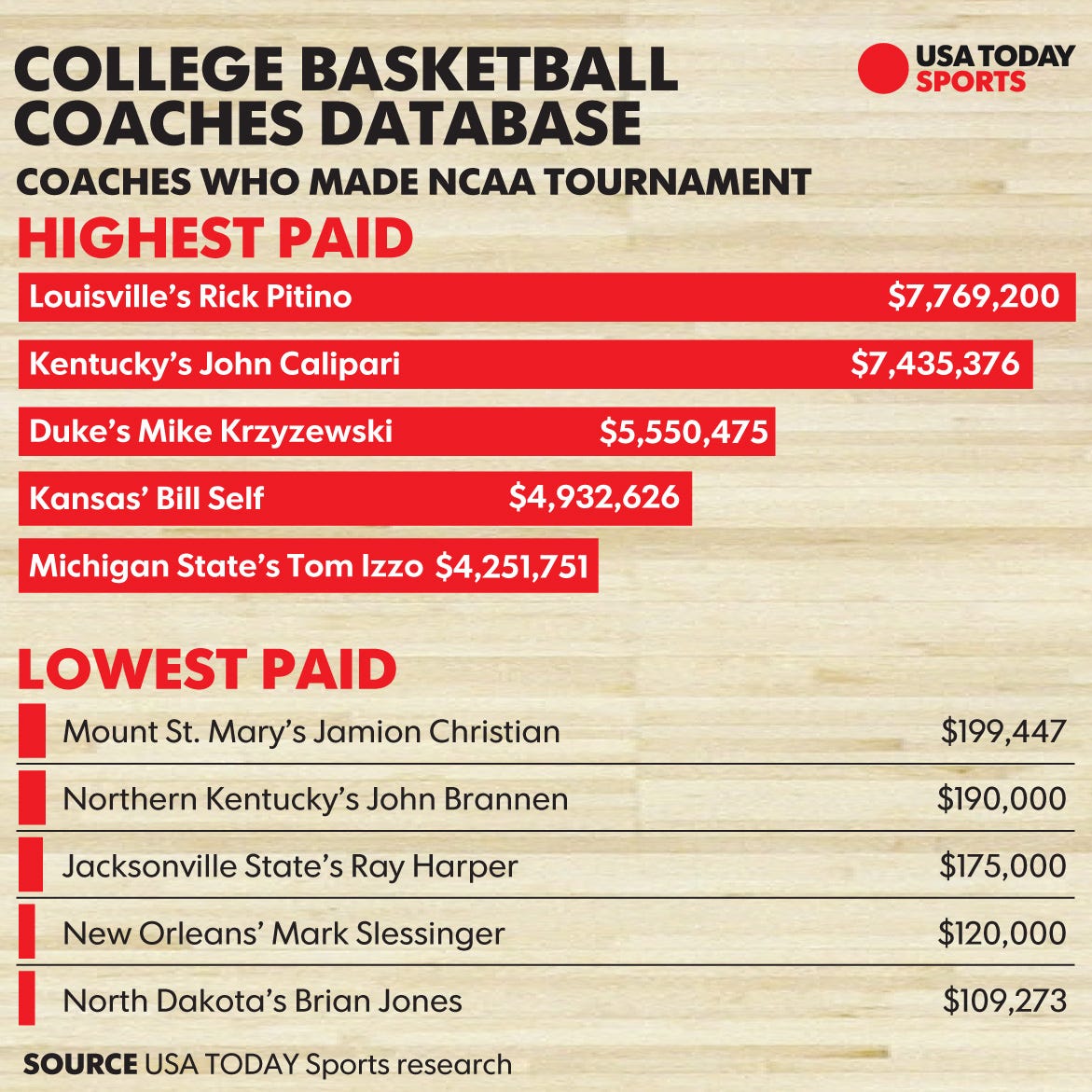

What NCAA Tournament coaches make: Salary database

“We had a high limit, and we went to that with Buzz where we didn’t feel like we could do more, and we were very transparent about it,” said Babcock. “He actually took a pay cut to come here. We have different levels of investment we can make (in different sports), but with Buzz we stretched it as far as we could go.”

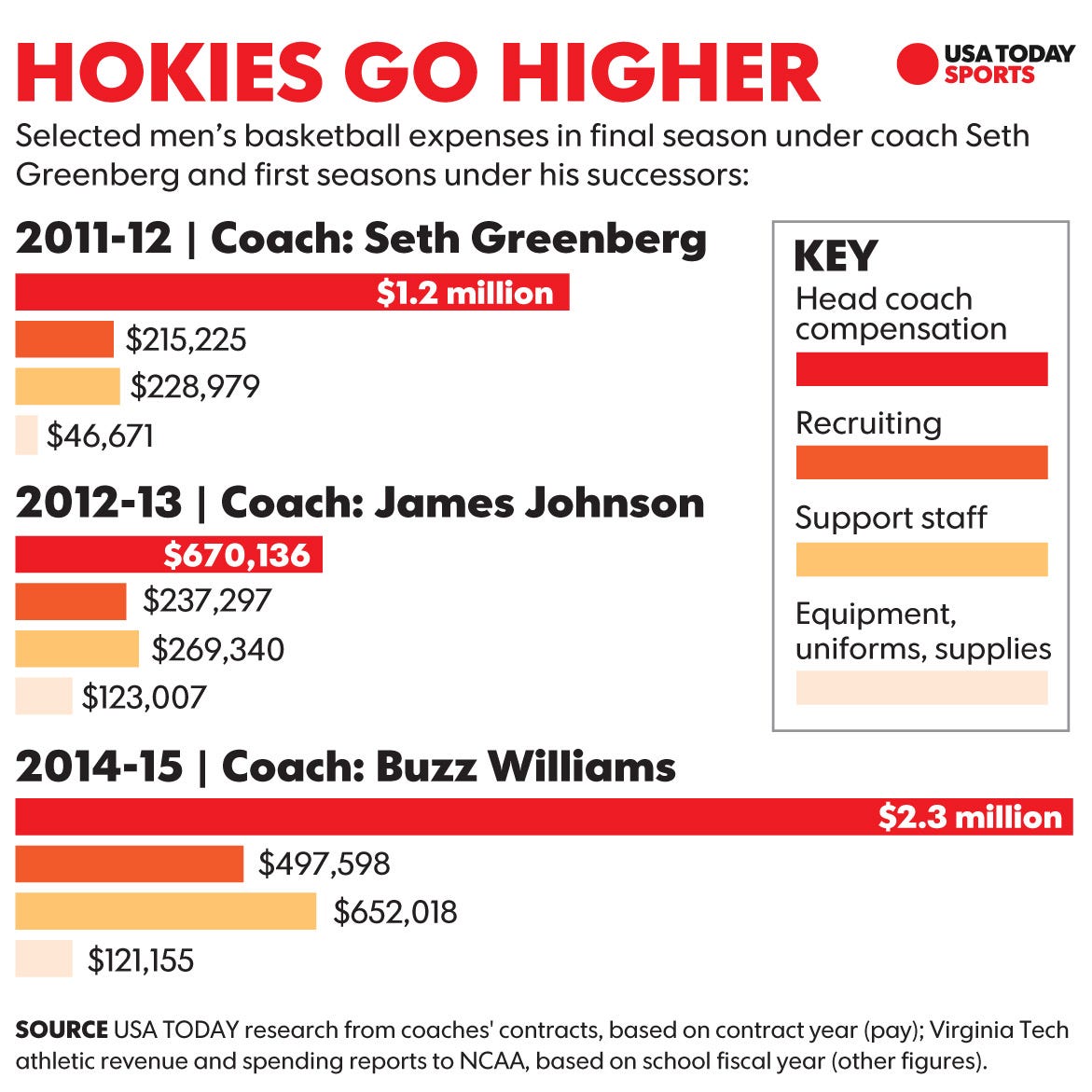

Though hiring Williams would require Virginia Tech to significantly expand its financial commitment to basketball — Williams’ initial salary of $2.3 million was more than a 250% increase over his predecessor James Johnson while the school was still paying the buyouts of Johnson and former coach Seth Greenberg — the expense seems to be paying off. Virginia Tech finished last in the ACC in Williams' first season, but by his third the Hokies earned just their third NCAA tournament bid since 1986.

Though Virginia Tech lost in the Round of 64 to Wisconsin, 84-74, the team’s 22-11 record validated Babcock’s decision to pursue an expensive hire in basketball at a school whose athletic success, financial strength and branding has long been tied to football. And it’s a strategy other Power Five schools are trying to follow.

Last spring, TCU lured Jamie Dixon away from Pittsburgh, where he had won consistently for 13 seasons. The dividends have come quickly for the Horned Frogs, who were suddenly competitive in the Big 12 and made the NIT Final Four.

This year’s hiring cycle has seen Illinois hire Brad Underwood away from Oklahoma State, increasing the head coach’s salary from the $1.7 million it was scheduled to pay John Groce next season to $2.75 million, plus an increase of nearly $300,000 in the salary pool for his three assistant coaches, totaling $850,000.

Similarly, in firing Kim Anderson and hiring Cuonzo Martin away from California, Missouri is more than doubling its head coach salary ($1.2 million to $2.7 million) and increasing the salary pool for basketball-specific staff members by 22% to $1.1 million.

Though others have attempted similar tactics with mixed results — Auburn is yet to make the NCAA tournament in three seasons under Bruce Pearl, and Mississippi State hasn't finished above .500 in two seasons under Ben Howland — the fact those schools were even able to lure established winning coaches speaks to the increasing advantages Power Five schools are gaining over athletic departments that lack the revenue to throw money at their problems.

"Virginia Tech is traditionally a pretty good football school, so why would they choose instead to start focusing more attention on basketball?” said Rodney Fort, a sports economist and professor of sport management at University of Michigan. “If Virginia Tech is as good as they want to be in football, they’re going to have money left over because (revenues) are going to keep going up. What are they going to spend it on? They have to sit down with their university administration and decide that. I guess the answer at Virginia Tech was, let's get better at basketball.”

His own biggest advocate

Beyond the crude calculation of whether spending significantly more money on basketball is a bottom-line plus for Virginia Tech’s athletics department or merely a luxury for a school that attributed 13.1% of its athletic revenue from men's basketball in the most recent reporting year of 2015-16, Williams’ contract is a fascinating study in how a winning coach has used his leverage in very specific ways to improve a program.

Though Williams’ gravelly Texas accent and hardboot coaching background may not give off a vibe of sophistication at first blush, he is undoubtedly one of the most well-read and intellectually curious coaches in the sport. Unlike the vast majority of his colleagues, Williams does not employ an agent and negotiates his own contracts. Beginning at age 21 when he landed his first assistant coaching job at Texas-Arlington, Williams said he has annually filed public records requests for the contracts of every football and basketball coach at every Division I public institution to learn about how a contract should be written.

“I like studying it,” he said. “I don’t care about the numbers. I care about the clauses. In each segment of the contract, they’re all for the most part orchestrated and organized the same. So what I want to do is, I call it ‘best of class’. So in a particular article, I look at who has the best one in football and who has the best one in basketball and why is it the best?”

Williams’ most recent contract renegotiation following the 2015-16 season bumped his basic pay from the school to $2.6 million for this season with a $25,000 bonus for making the NCAA tournament plus academic incentives that could add another $40,000 to his pay. His total pay ranks among the top half of coaches in the ACC.

Williams’ contract language is heavily in his favor regarding buyout terms. If he were fired April 1, 2017, he would be owed $17.3 million, a number that declines proportionally as contract years roll off. By contrast, he would owe Virginia Tech $900,000 if he were to take another job now. That number declines to $750,000 on March 23, 2018 and continues to decline in future years.

Williams’ contract is also filled with perks that range from standard stuff (Blacksburg Country Club membership and use of two automobiles, replaced every two years, plus insurance) to specifically-written clauses that stretch beyond the norm in college athletics.

Williams gets 12 premium tickets for all home basketball games, 24 all-session passes to the ACC tournament, 24 tickets for every NCAA tournament game Virginia Tech plays and 12 premium tickets for home football games.

MORE COACH SALARIES:

NCAA Final Four may illustrate some of coaching's big perks

Louisville's Rick Pitino breaks own record for outside income

The missing numbers in Roy Williams' record book

Virginia Tech is also contractually obligated to reserve two seats on the team plane or bus for Williams’ immediate family members, and the University will “pay the reasonable expenses (of) all Williams’ immediately family members on up to five work-related trips per year with prior approval” from the athletics director.

Williams, who has four children, said staff members don’t have to ask to bring their kids or spouses around the office or to practice.

“I’d say 80%, 70% of our team is going to come from a non-traditional household, and part of my responsibility is to help model what it means to be a husband, a father,” Williams said. “I think it’s healthy for the organization.”

Virginia Tech also is contractually obligated to “sponsor the visa application for any foreign staff member as required by law for said staff member to lawfully work in the United States,” a clause written specifically for assistant coach Jamie McNeilly, who is Canadian.

Though those are typically items a coach would have autonomy over anyway, or have a handshake agreement with an athletics director, Williams prefers to put everything in writing.

“I never want, as we grow and as we improve and it turns into something we didn’t think it was going to turn into, good or bad, that the handshake changes or that it puts either of us in negative alignment,” he said.

Some of that sentiment may reach back to Williams’ break into the head coaching ranks in 2006 at the University of New Orleans, a program struggling to recover from the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. A year later, Williams resigned to join Tom Crean’s staff at Marquette, unsure whether he would get another opportunity to be a head coach.

Upon his departure, Williams sued the school, claiming it breached his contract by not fulfilling promises and basic services necessary to compete. The school filed a counter-claim to recover the $300,000 buyout in his contract. They eventually settled out of court.

Meanwhile, when Crean got the Indiana job the following spring, Williams was the surprise choice to succeed him after an intense week of interviews with school officials. He signed a memorandum of understanding on the hood of his truck, knowing he had little leverage to negotiate.

“I say this in the right way, but I knew it was a contract that was best for Marquette, and I signed it for no reason whatsoever other than they had huge guts to hire me,” Williams said. “But I told the AD, this will be the last contract I ever sign that I didn’t write.”

Williams exceeded expectations at Marquette, making five consecutive NCAA tournaments with Sweet Sixteen appearances in 2011 and 2012 and an Elite Eight in 2013. A rebuilding year followed, after which it became apparent to Babcock that Williams might be willing to move on. Virginia Tech had finished last in the ACC each of Johnson’s two seasons, and Babcock moved quickly to make the change.

“We were looking for a sitting head coach that could compete in the ACC and wasn’t going to look down the sideline and be intimidated by Coach K or Roy Williams,” Babcock said.

“We thought to get a coach in of Buzz’s caliber would make a statement in this league.”

In addition to Williams’ salary, Virginia Tech also had to commit more money for assistant coaches and recruiting.

In 2014-15 and 2015-16, Virginia Tech reported $848,630 spent on basketball recruiting, which almost equals what the programs spent in the previous four years combined ($913,554). In Williams’ first season, Virginia Tech spent $497,598 on recruiting, which was nearly $20,000 more than the football program spent on recruiting over the same time period.

Babcock attributes some of that to the health issues former football coach Frank Beamer had at the time, which prevented him from going on the road as much. But it’s also true that Williams insisted on increased use of private airplanes for him to make inroads for both the short-term and long-term in a region where he had no previous ties in recruiting.

“Buzz had said, ‘I’m not going to abuse it, but to really recruit well I’m going to have to have some private airplane travel,' which is pretty consistent in the Power Five,” Babcock said. “But we weren’t doing much of that.”

Williams said his travels around the region were invaluable to relationship-building and that being able to get around in a private plane was absolutely necessary, especially to and from hard-to-reach Blacksburg.

“I can’t spend time flying a commercial flight to recruit,” he said. “I need to be with my family, I need to be with our team, I need to have home base here daily no matter what’s going on.”

Williams’ first season was difficult, as the Hokies went 2-16 in the ACC. By Year 2, he had turned over 12 of the 13 scholarship players — “Suicide,” Williams said — and lost the season opener at home to Alabama State. But midway through that season, his message had clearly taken hold.

Though Virginia Tech missed the NCAA tournament, its 20-15 finish had given Babcock the confidence to engage Williams on contract extension talks. Williams earned a modest raise, but the key for him was the treatment of his assistant coaches.

Virginia Tech not only agreed to increase the salary pool for Williams’ staff by $70,000 from the original $725,000 for three full-time assistants and $325,000 for his operations staff, but every staffer under Williams’ direction will receive at least a 2.5% raise every July 1 for as long as Williams is employed as the Hokies’ head men’s basketball coach.

“If you’re producing, you’re under the umbrella of my contract,” Williams said. “I told Whit, ‘I want to quit saying the typical that the staff is so important. I want to prove it. I want them in it.’ ”

Return on investment

In Williams’ office, a dry erase board lists items remaining on his so-called “bucket list,” which include running a marathon, attending a Kentucky Derby and a U.S. Open tennis tournament and building a relationship with former Dallas Cowboys coach Jimmy Johnson.

The opposite wall is covered with hundreds of pictures of Williams with former players, friends, and celebrities who have crossed paths with him at one time or another. Williams is obsessed with photographs, an outgrowth of time spent with a grandfather who couldn’t read and relied on pictures to tell the story of his world.

Williams, in fact, pays local photographer Christina Wolfe out of his own pocket, giving her access to every aspect of the Virginia Tech program so that the beginning-to-end progress of each season’s journey can be cataloged through images.

Here’s what that progress has yielded for Virginia Tech, beyond the increasing win totals and respectability in the ACC:

► Though the program’s expenditures have risen from $5.84 million in 2011-12 under Greenberg to $9.5 million in 2015-16 ($715,189 of which was severance pay, which is slowly coming off the books), attendance has spiked from 4,812 in Johnson’s last season to 6,658 in 2015-16 to 7,476 this year including five sellouts (9,567).

► Demand has increased to the point where Virginia Tech has installed premium courtside seating and will, this summer, begin removing some of the original wooden seats from 1962 and replace them with plush modern seating to be sold at premium prices.

► More visibility on national television, with eight games on ESPN or ESPN2.

► And private contributions directed to basketball totaled $1.738 million in 2015-16, up from $412,711 in 2012-13 and $771,623 in 2013-14. Much of that money has gone into upgrades for the program’s practice facility and weight room, with more in the planning stages. Williams has alone raised more than $2 million since arriving at Virginia Tech, nearly all of which he attributed to nine large donors with whom he has built relationships. “And I haven’t asked for any of it,” Williams said.

► Desiree Reed-Francois, the deputy athletics director, said showing ambition in basketball has also helped recruit other coaches to the school. “When we hired Buzz, it made it easier to hire Justin Fuente,” she said, referring to the Hokies’ football coach who won ACC coach of the year honors in his first season. “Strong leaders want to be around other strong leaders. It’s like when you sign a blue-chip recruit, it sends a message to your next recruit.”

When Babcock hired Williams, he projected how much more money could be generated from hiring Williams, knowing it would stretch his budget and that the price of success for Virginia Tech would continue to increase if Williams started winning. Following the 2015-16 season, Babcock approached Williams about renegotiating the contract, which in addition to covering pay increases to Williams and his staff, added $100,000 to the program’s recruiting/travel and operations budget.

“Buzz exceeded my expectations in Year 2, and he exceeded them again this year,” Babcock said. “Being in the NCAA tournament is a big deal for us, and I hope we become regulars. I’m pleasantly surprised it happened quickly, but I’m not surprised. That’s the kind of coach we hired and why we did it.”

Any future contract negotiations are likely to center around Williams’ plans for growing the program, as he claims the numbers on the contract are not as important as his alignment with the administration on what it takes to succeed.

“This is really important to me,” he said. “I don’t need any more money. I made more money than I ever dreamed of, and if you want to know the truth, on the second day of the month my (accountant) draws everything out of my account. I get $50 a day and my wife gets $150 a day. She has a debit card, the title of her account is ‘Mama’s Money,’ the title of mine is ‘Daddy’s Money.’ I’m doing none of this for money.”

But it’s also true, over time, that other schools may attempt to lure Williams to a place with more tradition or recruiting advantages. After all, there are only so many coaches who have proved themselves to be worth the kind of money he is making at Virginia Tech or could make elsewhere. And the number of schools who can pay that amount of money is increasingly limited to the Power Five.

At least at Virginia Tech, it’s now proved that a football-oriented school with those kinds of resources can bet big in basketball and pull off a dramatic turnaround. And with several Hall of Fame coaches likely to retire from the ACC in the next several years, Babcock believes the window to become consistent contenders is just now opening.

“We felt like we could be very good in basketball, too. And why not try to be the best you can be in all 22 sports?” Babcock said. “What I didn’t love for Buzz’s sake is the criticism he took for taking this job, and it probably still motivates him. We’re in the ACC, we’re in the Power Five, we’re in a region of the country where you can get players, and it had happened in small doses here before. I wonder if people will now turn around and say, it was actually a really good decision for him to come here.”